Museum of the Peasant Family | Church of St. Nicholas (Museo della Famiglia Contadina | Chiesa di San Nicolò)

Highlights

The museum is housed in the Church of St. Nicholas (or of Battuti).

On display is important evidence of peasant life in the past.

• The history of the building (written (in italian) by Anna Mainardi Scarampi)

The copy of a map of 1764 shows us the plan of the castle of Montaldo Scarampi and the walls surrounding the village at the top of the hill (Montis altus).

The “Fence” was the name that included the whole territory within the walls. On the north-west side, within the enclosure, was a church, dedicated to St. Nicholas, later called the Church of the Battuti ('Bati').

Behind the church and bordering the walls was the cemetery.

The castle suffered a fire at the end of 1700s (according to the testimony of De Canis) and gradually everything fell into ruin.

The bricks and recoverable materials were used to build new houses, and nothing remained to testify to such great power.

The only one preserved was the church.

It was already deconsecrated when it was made suitable to house the Kindergarten in 1923. In the first part of the nave the hall was made to accommodate the children, a wall divided this from the accommodation for the nuns, this was arranged on two floors with a central staircase. On the first floor a room and kitchen in the apse, on the second floor three small rooms.

The first president of the kindergarten owned the Montaldo furnace: Giovanni Battista Binello, who donated bricks for the garden wall and for the floor with crawl space for the church. Probably, during this period, the facade was also embellished according to the taste of the time, as we see it on some postcards.

The rainwater cistern, which can be seen in the hallway today, was then outside in the garden surrounding the building. From 1936 and for some years, during the summer months, this was the home of the Heliotherapeutic Colony, for all the children of the village. In 1954-55 a 'classroom was built adjacent to the church with the corridor that covered the old cistern (drinking water had arrived-cost of the work £. 9,000). In 1956, another floor was built above the classroom to give more suitable housing for the Rev. Sisters. New pews were purchased and the furniture redone.

During this work, the decorative pediment of 1923 was torn down, and the building had a single facade made more modern, in which almost nothing now remained of the memory of the old church. In 1963, the Sisters were retired and the Kindergarten closed.

We thus come to the present day. In 1995, the municipality presented a project to restore the building by including it in a community path of small museums for the enhancement of the area. The project supported by the G.A.L received funding from the European Community, and thus restoration work was able to proceed.

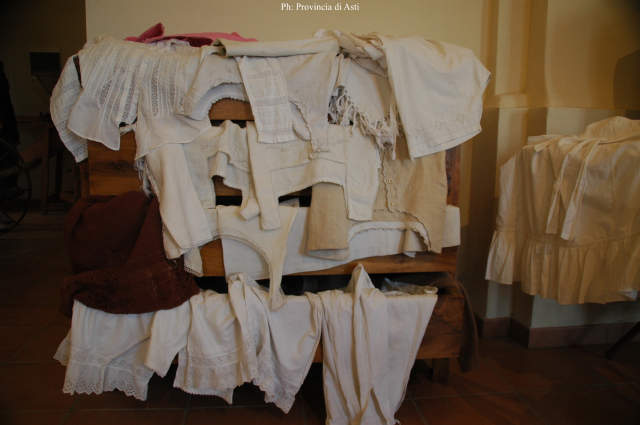

With the superstructures removed, the simplicity of the single nave that constituted the old church of the 'Batì' was presented to us in all its beauty. Thus, in July 2001, this museum was inaugurated, which aims to retrace the life of the peasant family through clothes: starting from the wedding, the baptism of the babies, the feast, to everyday life: the clothes of toil and work, of school, the kindergarten uniform.

The tools and objects with which the Museum is being enriched are the witnesses of life in Montaldo in the early 1900s and have all been donated to the Museum, a sign that it has become for the population the place of historical memory, the symbol of those values always necessary to build the future.

• The path

The visit to this museum aims to introduce us to some aspects of the country's life in the first half of the 20th century. We do this journey backwards, mainly by following fashion.

We begin with the wedding dresses: the first are from a wealthy couple in 1910, the others are from peasants who married around 1930. The suit, with the men's "redingote” jacket, was cut and sewn by a tailor's shop in Turin for the local gentlemen in the turn-of-the-century style while the men's suit from the 1930s, in a more modern style, was made by a good tailor in the village. At that time, there were many tailors and seamstresses, clothes were made to measure, and, depending on the skill of the tailor, he was made to make formal or business suits, partly because the less good tailor cost less.

Note how women's dresses were all shortened as fashion changed. The richest bride married in a white dress, and the wedding was celebrated on Sundays at the high altar. The poor used the black dress and were married on weekdays at the side altar of Our Lady. These clothes were kept carefully because they were to be used for all the important ceremonies of life. From the wedding onward, one wore dark clothes and black was the predominant color.

Baptism was another important moment. Babies were baptized as early as possible. Wrapped in swaddling clothes, they were laid in the 'porte-enfants' and brought to the church by the 'midwife' (midwife) followed by the father, godfather and godmother. The mother would stay in the house for 40 days and come out only after purification; a religious rite that has now disappeared. Of particular interest among the other “feast” dresses on display is the women's cape, made of heavy black embroidered cloth, from the second half of the 1800s. Under the dresses there was an abundance of blouses and petticoats. Brides-to-be spend much time, especially in winter, sewing and embroidering the trousseau (Fardél). First they wore the woolen or plush cotton knit for the poorer, then the sleeveless “shirt” of more or less coarse cloth; over this the petticoat of wool for the 'winter, of cotton poplin for the summer.

A fine example of embroidered flannel “cotin di sota” in 1800 is presented. Underpants were long for both men and women. Abundantly embroidered long-sleeved white shirts were “giac da noc”, night jackets. Men also wore a long night gown, and for those who could this gown was made of linen, the finest fabric. Remember that at that time the man was always considered superior to the woman. Let us turn to the accessories on display: a silk scarf from the 1800s is valuable. Various examples of quefe or Mass veils, then shoes, bags, gloves.

Note how there were accessories for mourning days. Special items included an embroidered parasol and fan from the 1800s, hair curling irons, pens, and nibs. One item that was not missing from homes was a sewing machine.

From the festival we move on to work: the work of the fields. On display are plows, harrows, a machine to be hitched to oxen for sowing, scythes and sickles for hay and wheat, ropes for sheaves. The copper sulfate machine, one of the first wine pumps, the wine press, demijohns, wine bottles, filters for muscatel etc.

Hanging on the old coat rack were work clothes worn out from use. The woman always wore an apron and a handkerchief on her head. In winter, men wore capes and women covered themselves with a woolen shawl.

Note a square fringed shawl from 1850; this shawl was also used to wrap children and better shelter them from the cold. On the feet are clogs and clogs made of leather with wooden studded soles and woolen socks.

Among the household items on display are: oil and acetylene lamps, grinders and coffee roasters that most often roasted barley which was the coffee of the poor, irons. A 3-plate stove:, earthenware or copper pans, brunsin for barley coffee, enameled pots. Only later would aluminum arrive. In the draining table various dishes. (Remember that the floors were brick and absorbed water).

For washing, from dishes to linens to the person, there were basins, basins, wooden slatted tubs (garocetta and sebbi) of various sizes, later replaced by zinc ones such as buckets for bringing up water from the well. Those who owned a bicycle were already lucky, and for the rare trips that were typically emigrant journeys, canvas bags and cardboard suitcases were enough.

Children went to kindergarten in blue and white checked pinafores for boys, red and white for girls. In the basket they carried their lunch: bread, an egg, a fruit. The sisters would prepare soup for everyone.

For walks or processions the children wore the uniform consisting of the white pinafore with blue collar and bow, sugar-paper colored cloth cape and blue beret. They walked to school in a black apron and white collar, the satchel was made of cardboard or wood, and pens, nibs and ink were used for writing. The teacher also had to wear a black apron. Black dresses and aprons also had the advantage that they could be washed more infrequently because less dirt could be seen (water was a precious commodity and was used sparingly).

White collars, sometimes even cuffs, were detachable so they could be washed more often. Toys were rare and only for the well-to-do, but imagination was huge: with little you had a lot of fun. Even the letter carrier had his nice sugar-colored uniform: the pants, shirt, jacket, and tie. On view is a photocopy of letter carrier Battista Destefanis' workbook dated 1875, when Montaldo Scarampi was still in the province of Alessandria. Note the strictness of the rules.

The visit ends here. With the simplicity proper to the peasant world, we wanted to open a window on our past, so that the memory of things and values will serve for the future of new generations.

See also

News from Montaldo Scarampi

- Discover the latest news posted on the website of the Municipality of Montaldo Scarampi

https://www.comune.montaldoscarampi.at.it/it/news

Events in Montaldo Scarampi

- Discover the events posted on the website of the Municipality of Montaldo Scarampi

https://www.comune.montaldoscarampi.at.it/it/events